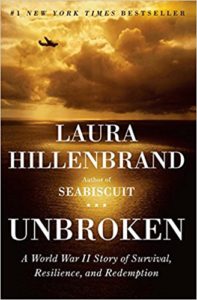

Book Review: Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

“If I knew I had to go through those experiences again,” he finally said, “I’d kill myself.”

Louis Zamperini said these words after his release from a Japanese concentration camp at the end of WWII.

His story was recently told by author Laura Hillenbrand in her best selling biography, Unbroken. If it was a fiction, it would be going too far. Nearly unbelievable. Gripping, almost cinematic, pushing the boundaries of realism. Yet it is true. Louis Zamperini is real, and his story is impressed deep into the furrows of history.

His story from a purely biographical perspective would warrent interest enough: son of italian immigrants, a troubled boyhood rooted in trouble and rebellion, Louis never had an age in which he was a passive observer of life. Even his boyhood pursuits seem to push the boundaries of a fiction character. At the age of two, he bolted off the caboose of a train, then strolled up the track after it in perfect serenity, uninjured, to say to his frantic mother after the train could finally stop itself, “I knew you’d come back.”

He started smoking at the age of five and drinking at eight. He impaled his leg and severed his toe (which had to be sewn back on by a willing neighbor), nearly drowned in a gallon of turpentine, stole entire cakes and kegs of beer from the houses nearby and on one occasion, in revenge for not being invited to a dinner party down the street, broke into the unwelcoming house, bribed their Great Dane with a bone, and cleared out the entirety of the ice box.

Later in life, Louis would retell his boyhood adventures, almost always ending with:”…and then I ran like mad.”

And he didn’t stop running.

He later wrote: “It was the recognition, nobody in school, except for a few of my buddies, knew my name before I started running. Then, as I started winning races, other kids called me by name. Pete told me I had to quit drinking and smoking if I wanted to do well, and that I had to run, run, run….Overnight I became fanatical. I wouldn’t even have a milkshake.”

Eventually, Louis Zamperini finished in a tie against record holder, Dan Lash, in the 5,000 meter race, thus qualifying for the 1939 Summer Olympics in Berlin. At the age of 19, he is still the youngest American to ever qualifiy in the 5,000 meters.

But Zamperini’s career, was soon to end.

In 1941, he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps, and all he knew began to fall apart around him. Harrowing escapes, blood-chilling battles, images never to be erased, and the quick and painful loss of many of his friends introduced him to the bloody terrors of war.

That is why Unbroken is more than just a chronicle of Louis’ lifetime events, but the journey of a man pushed to every boundary of emotion, dignity, and life itself. It is a rolling, harrowing journey of hope and despair, life and desecration, starvation and euphoria, courage and debilitating trauma.

After a defective plane landed him and his team in the middle of the Pacific ocean, Louis and two other men, Russell Phillips and Francis McNamara, were the only two survivers. They lived on a life raft for a month a half, surviving on only captured rainwater, the rare fish they could capture eaten raw, and two albatrosses that landed on their raft, which they tore open and divided between them, allowing McNamara (Mac), who was the weakest, to drink the blood. They were strafed multiple times by a Japanese bomber, which pelted hundreds of bullet holes into their already deflating raft, and were kept awake at night by the the shudders of the rubber beneath them, as hungry sharks rasped their backs along the bottom of the raft. Mac died after 33 days.

On day 47, they reached the Marshall islands and were immediately captured by the Japanese Navy. Transferred from camp to camp, Louis endured cruelty beyond imagination, beatings, starvation, illness, mockery, and then something worse than all: “On Kwajalein, the guards sought to deprive them of something that had sustained them even as all else had been lost: dignity. This self-respect and sense of self-worth, the innermost armament of the soul, lies at the heart of humanness; to be deprived of it is to be dehumanized, to be cleaved from, and cast below, mankind.”

Hillenbrand continues: “Dignity is as essential to human life as water, food, and oxygen. The stubborn retention of it, even in the face of extreme physical hardship, can hold a man’s soul in his body long past the point at which the body should have surrendered it.”

Louis, who had measured a fit and lean 155lbs when first enlisted, was now weighed at less than 80 (some estimates as low as 67), at the height of 5’11”.

He was eventually transferred to a prison camp worse than he could have imagined: Ofuna. This camp was under the grip of one of the most tyrannical, evil and sadistic men of history, known by the prisoners there as The Bird. The Bird took a particular dislike of Louis – this famed Olympic athlete, famous in his own country, respected by his men, and promoted to officer at a young age – Louis had everything from which The Bird had been deprived. He targeted Louis in his cruelty again and again, making his life a living hell, and instilling in his heart, a deep and boiling hatred. In the midst of one, particularly cruel infliction by The Bird, “He felt his consciousness slipping, his mind losing adhesion, until all he knew was a single thought: He cannot break me.”

I have neither the time nor the words to express the horrific events that went on in these camps. Men starving to death as they labored for eighteen hours straight on nothing but a golf ball sized clump of infected rice, or half a bowl of diluted seaweed. Most of the men there – young, most about six feet tall – weighed less than 100 pounds, and many were under 90. Sickness reigned. 600 men shared 12 benjos, which often overflowed with blood and diarrhea, beatings were merciless and often without cause, and if a man was too sick or weak to work, his rations were cut in half.

When the war ended and Louis was finally rescued, he was haunted by memories, nightmares of The Bird, and, like many of his post-war comrades, eventually sunk into alcohlism and depression. “For these men, the central struggle of postwar life was to restore their dignity and find a way to see the world as something other than menacing blackness.” The only thing that kept him alive was a single pin-point of reason and purpose: Louis wanted to kill The Bird.

Louis’ story didn’t end with the war.

Why Should I Read It?

I don’t want to spoil the ending (which you wouldn’t know if you have only seen the movie), but this book is certainly worth the read. If you’re wondering if you should read it, read it. I think every person should. It changed my perspective of everything – life, hope, courage, suffering, pain, happiness. It is a story concentrated deep in every tenant of human life, focused keenly on its meaning, dripping with purpose, survivalism, impossible questions and gripping answers. It is a riveting story that is rivetingly told.

“Ferociously cinematic,” as one reviewer put it, “…you don’t dare take your eyes off the page.”

You don’t have to love sports, or history, or events of the wars that shaped our nation (though this book surely has enough to satisfy these fronts). All you must love is a story well told. One pressed deep in life, and meaning, and the why’s of existence. One that demands to be told.

One that is true, of a man unbroken.

*Photos taken from the book